Superannuation and climate change: Better returns for a better climate

03.04.2024 - 02:51

Mandala's report, 'Superannuation and climate change: Better returns for a better climate' in partnership with Future Super, examines the economic impact of market failures in superannuation performance standards. It identifies opportunities to unlock long term economic uplift through reform of these standards. Climate change will reallocate capital across the economy. Australia’s $3.4 trillion of superannuation savings will be impacted by this transition and determined by Australia's policy settings. There is significant opportunity for regulatory reform that drives returns and facilitates a broader role for the superannuation industry within the transition to net zero – and more particularly to address the market failures and time inconsistency that emerge from current regulatory design choices. Such reforms would recognise the core responsibilities of superannuation and the economic and policy priorities facing Australia.

Climate change will reallocate capital across the economy. Australia’s $3.4 trillion of superannuation savings will be impacted by this transition and determined by Australia's policy settings.

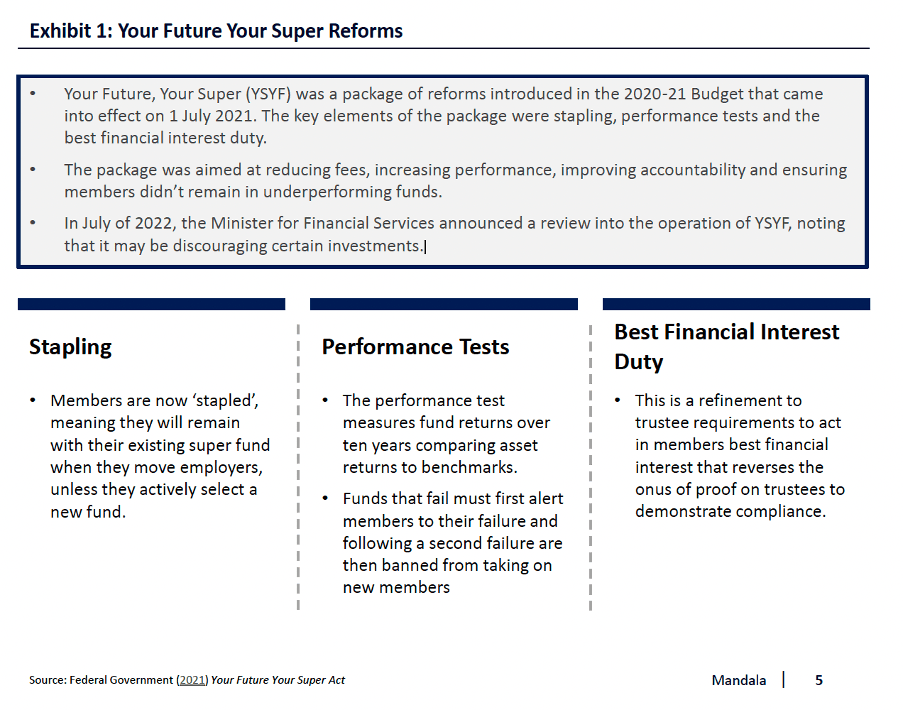

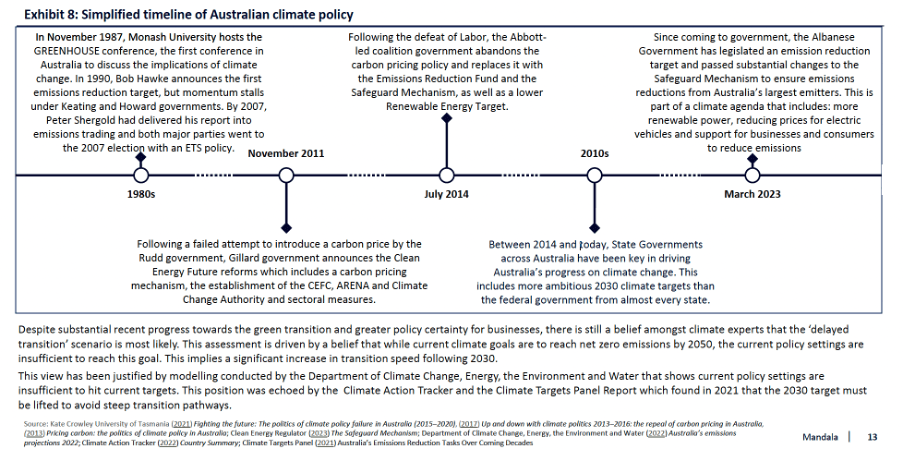

The previous government’s Your Future, Your Super (YSYF) were well-intentioned but have led to unintended consequences and perverse outcomes that hurt people saving for their retirement, our climate transition and economy.

These reforms aimed to increase member engagement, reduce fees, increase performance, and hold trustees to account for the decisions they make. But, as the government has acknowledged, the issues raised by the reforms have necessitated a review.

The Your Future, Your Super performance tests benchmarks each asset class against a standard backward-looking benchmark. Failing this test will close the investment option to new members and put in the fund’s future in jeopardy. This poses a challenge for ethical funds.

If a fund refuses to invest in big tobacco, arms dealers, environmentally polluting firms, or the banks that fund them, they will deviate from the benchmark – particularly when the global conflicts are pushing up profits for fossil fuel companies – and be penalised for doing so.

The consequence is significant: the Your Future, Your Super reforms incentivise more investment in businesses and industries that delay Australia’s climate transition and hurt the social good.

If policy settings allow our superannuation savings to invest in this transition, the returns to savers will be higher, the benefits to the environment will be larger and the benefits to the economy will be greater. The outcomes for savers, the environment and the economy will be pulling in the same direction.

Benefits for savers

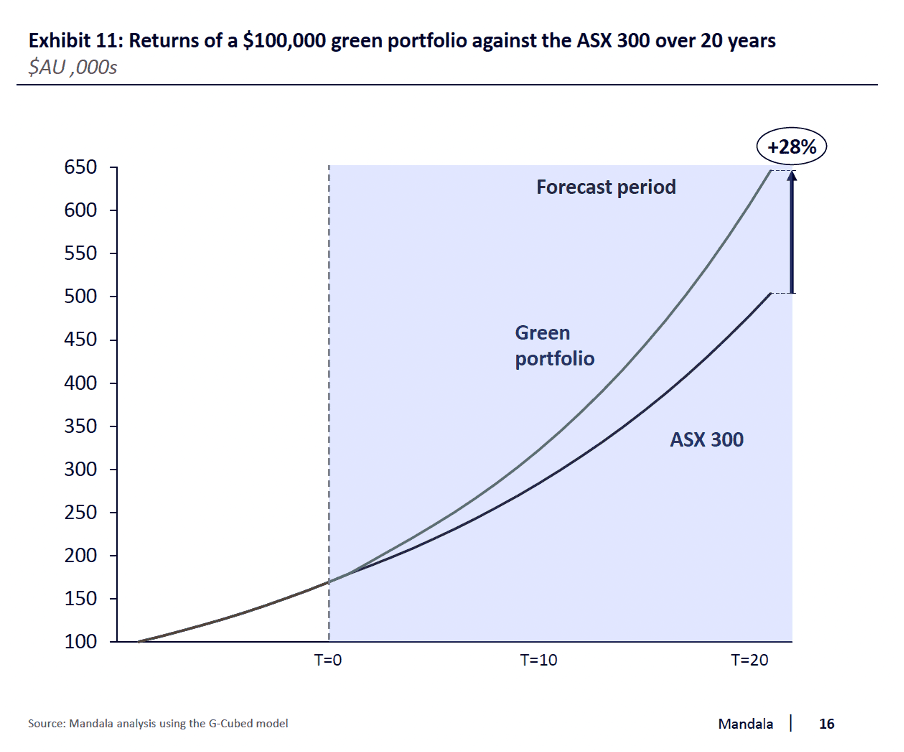

Savers in green funds receive returns 15% higher over 10 years and 28% over 20 years as markets begin to price in climate risk

Increased investment means higher wages over the next 10 years

Benefits for the environment

Increased investment in green sectors will reduce funding costs for businesses supporting the transition and incentivise green investment

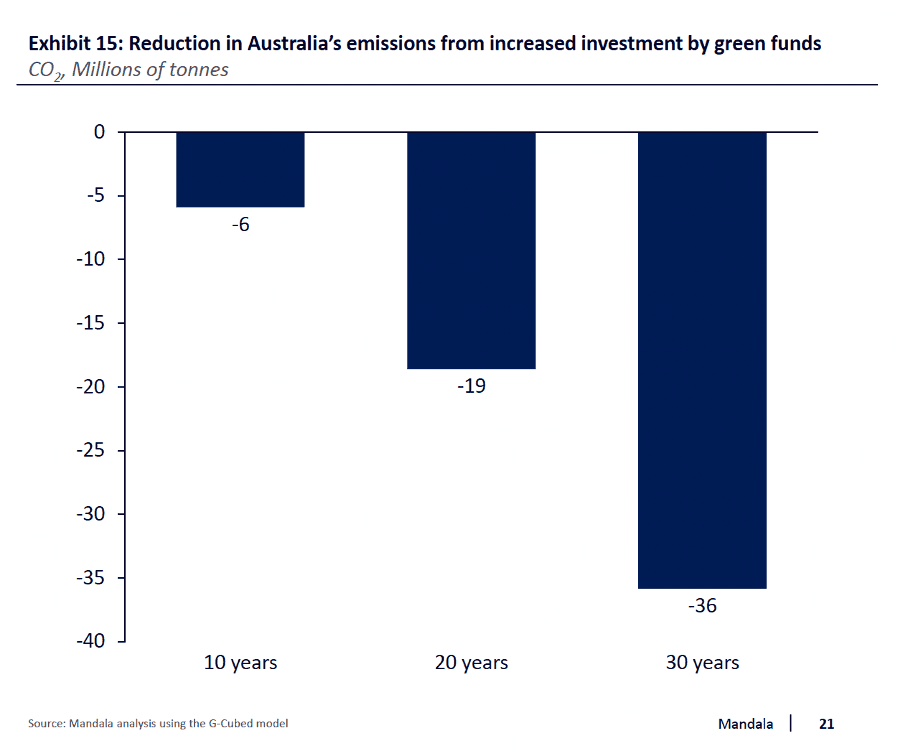

Mandala’s modelling found this will result in a 36 million tonne reduction in CO2 emissions

Benefits for the economy

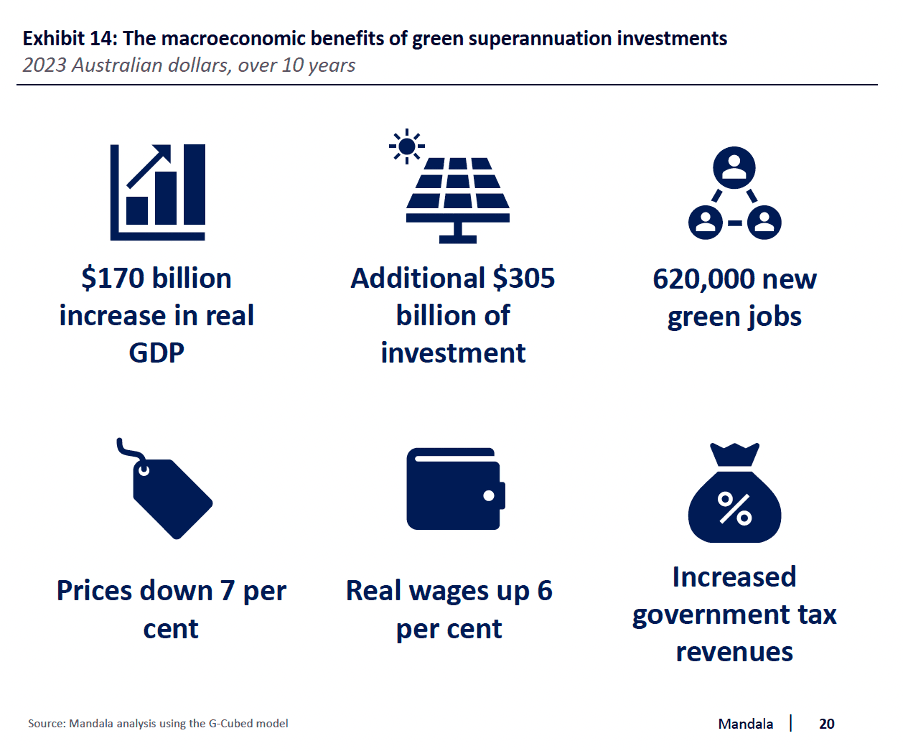

Mandala’s modelling found this increased investment will increase real GDP by $170 billion over 10 years, create 620,000 new green jobs and reduce inflation 7% over the same time period.

However, if regulatory barriers prevent superannuation savings from supporting this transition, retirement savings will be lower, the transition will be slower, and the adjustment costs to the community will be greater.

As always, the most disadvantaged Australians will suffer the most.

Your Future, Your Super Performance Tests are limiting funds from fully participating in the green transition

Your Future Your Super introduced Performance Tests to ensure members did not stay in underperforming funds

The Productivity Commission’s (PC) Inquiry into the efficiency and competitiveness of Superannuation found that structural flaws like unintentionally having multiple accounts and having entrenched underperforming funds were harming members.

The PC found 42 funds performed below a benchmark of their own portfolio with 29 under-performing by more than 0.25%. These funds have more than 5 million members. These members tended to be younger and have lower incomes. Underperforming funds are costly for members. The difference between top quartile returns and bottom quartile returns is $502,000 for the average member over their lifetime.

To minimise the impact of multiple funds and under-performance, the PC had two recommendations: stapling; and outcomes testing for all funds. The recommended structure of the test was similar to the test introduced in YSYF reforms.

The performance test has significant consequences: It is short term and ignores member preferences

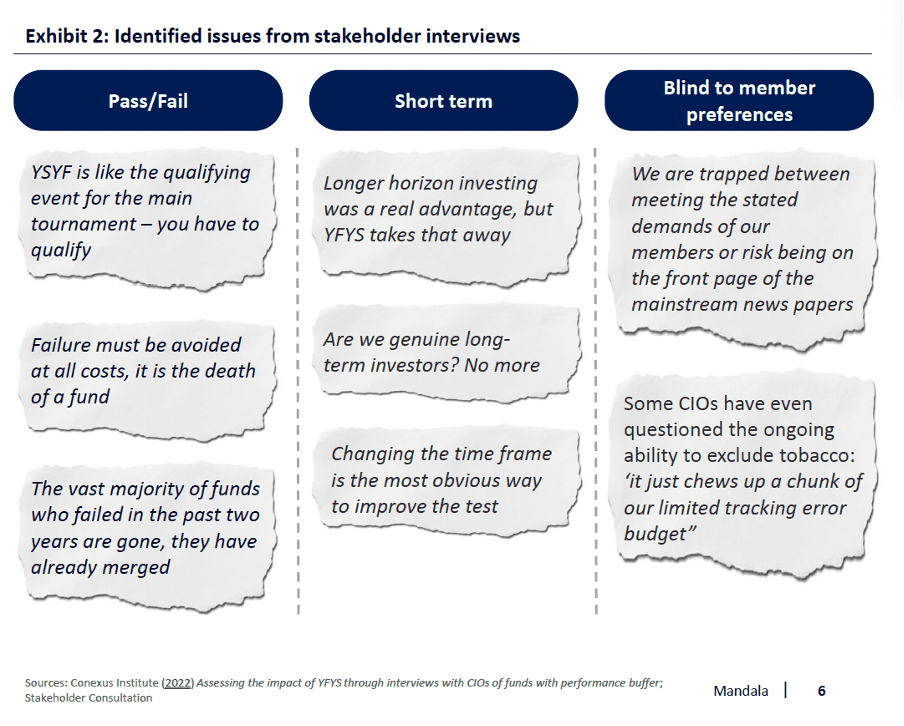

Failing performance tests forces funds to notify their members of underperformance and inhibits them taking on new members. These are dire penalties; and mean that CIOs must pass at all costs.

The current tests also impede the deployment of capital into assets with longer term investment profiles. The ten-year time frame requires upfront returns and punishes temporary blips below benchmarks, regardless of the long term pay-offs. This means that products like renewables, with long term return profiles and high upfront costs, are heavily discouraged.

The test is also blind to member preferences. Funds are restricted from investing in line with member values. If a member opts into a fund with an ethical approach, e.g. a green fund, the fund is tested against benchmarks that are not green. This means that after one off events, the fund may fail the test, even if the investment strategy is strong over the long term and endorsed by members.

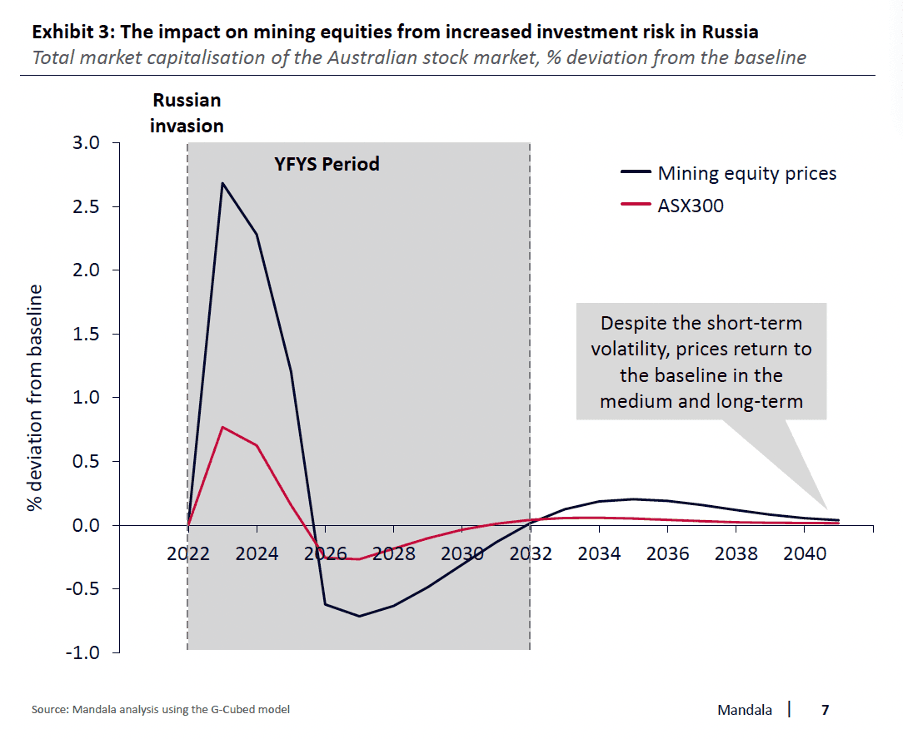

The 10-year time horizon in YFYS means funds are forced to react to short-term volatility

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has significantly increased equity prices of Australian fossil fuel firms. However, this increase is temporary and will result in no long-term impact.

If Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted global investors to demand a 50 per cent risk premium for investing in Russia – a conservative assumption given the sanctions that are in place – Australian equity prices in mining would return to the baseline scenario.

The 10-year time horizon built into the Your Future, Your Super regulations is unrealistic given what we know about economic and financial shocks. Over the long term, these significant shocks will have limited impact. The 10-year time horizon means that funds are forced to react to these shocks.

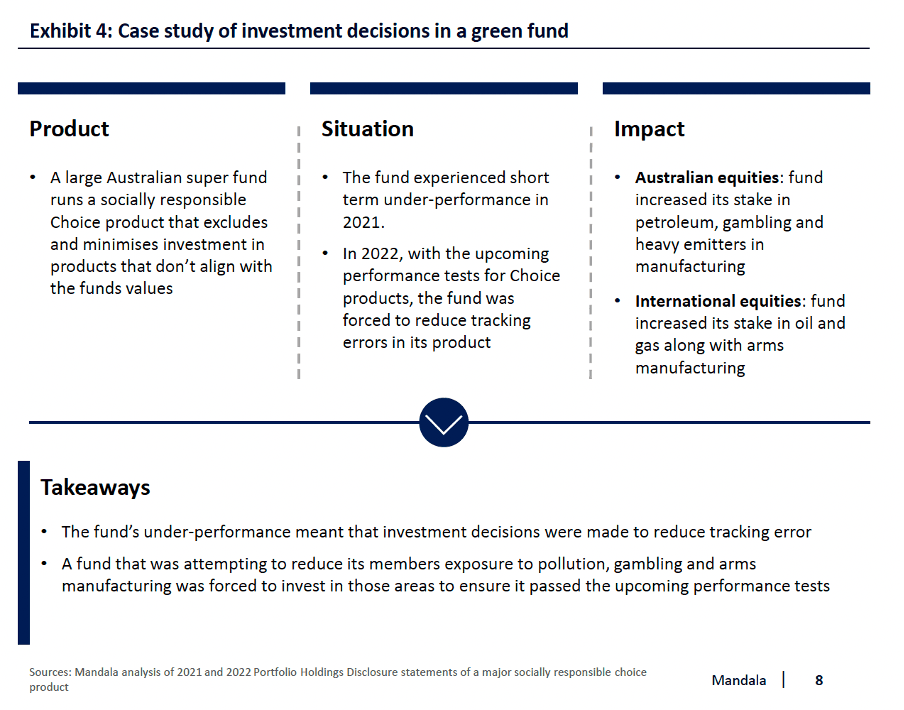

Performance testing is already warping the decisions of CIOs on gambling and pollution

The consequences of failing the test, their relative short termism and blindness to member preferences mean CIOs are incentivised to hug indexes by reducing tracking error to ensure they pass.

Tracking error is a measure of the variability between returns of a portfolio and returns of a benchmark. Tracking error indicates how closely a portfolio tracks the index it is benchmarked against. The higher the tracking error of a portfolio, the higher the likelihood a portfolio will perform below the index. This is true even if the portfolio outperforms the index on average or in the long run.

Green funds that exclude or reduce investment in polluting products have a higher tracking error because they are unable to recreate the index they are tracking. When these funds are in danger of failing performance tests, they are forced to reduce their tracking error by increasing their investment in polluting products.

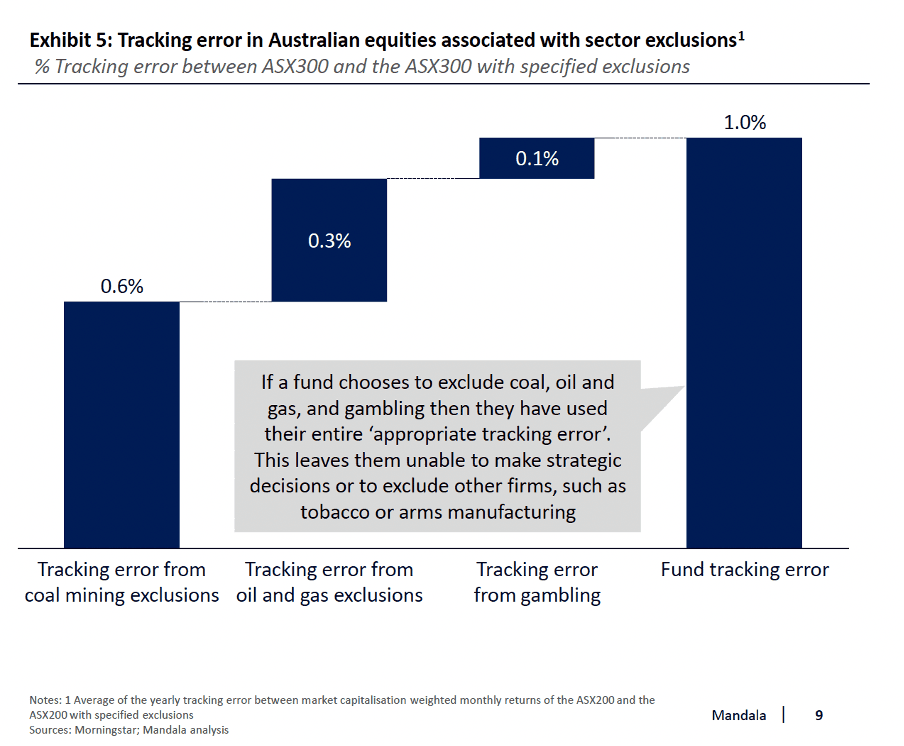

The tracking error incurred by excluding high-emission businesses puts super funds at risk of closure

Stakeholder engagement found that CIOs consider tracking error as a budget. Each deviation they make from investing in the index adds to their tracking error and ‘uses up’ the budget. Green or ethical funds that wish to exclude polluting, gambling or tobacco industries find that their tracking error budget is quickly used up. This means that their remaining portfolio must mimic the index as closely as possible, reducing the ability of these funds to make strategic decisions and align with members.

Stakeholders indicated that funds run a tracking error of around 1-1.5% in Australian equities. Conexus estimates that the maximum tracking error is around 1% for the asset class.

Mandala has found that the tracking error associated with excluding coal mining was the costliest at 0.6% while the error associated with excluding oil and gas was 0.3% and excluding gambling was 0.1%. This means that green funds with exclusions must take on unsustainable risk.

Climate risks will structurally change the Australian economy, but superannuation funds that are forward-looking have the opportunity to benefit members

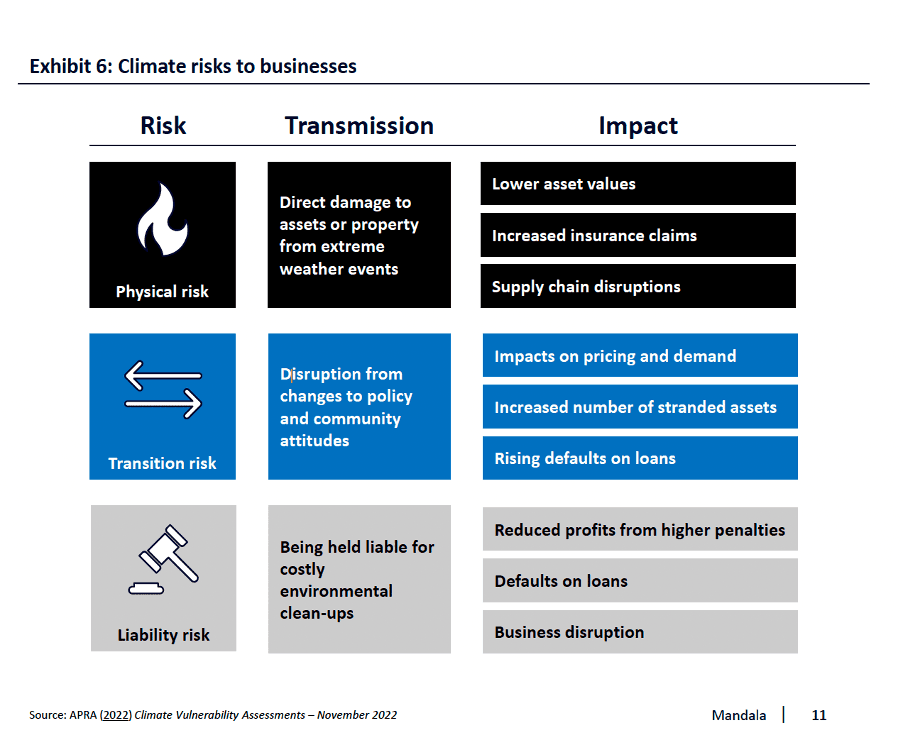

Climate change drives risk that will reallocate capital in the Australian economy

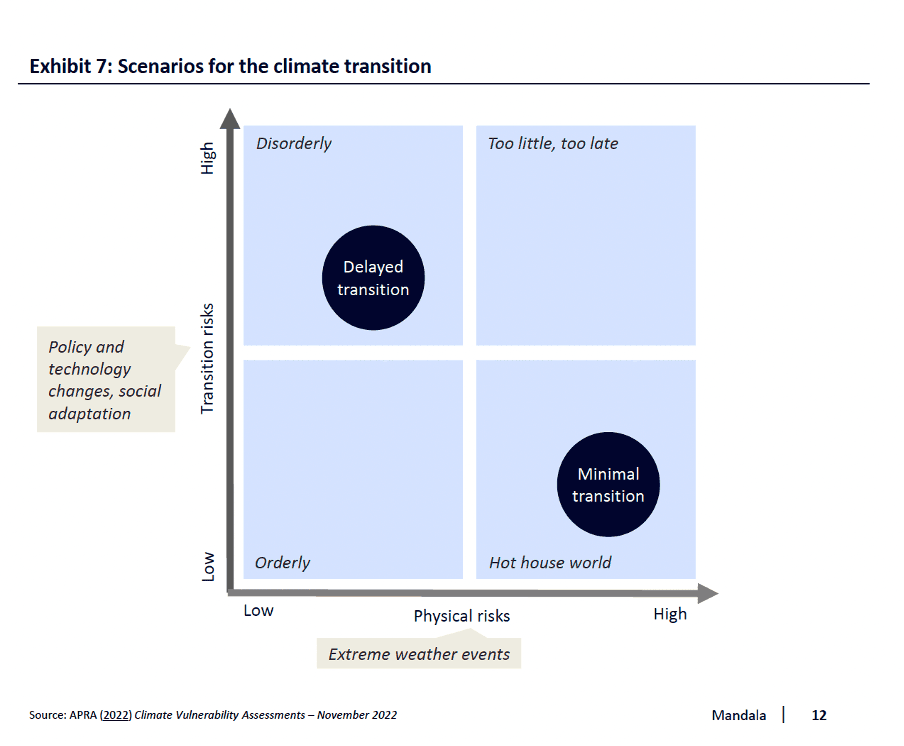

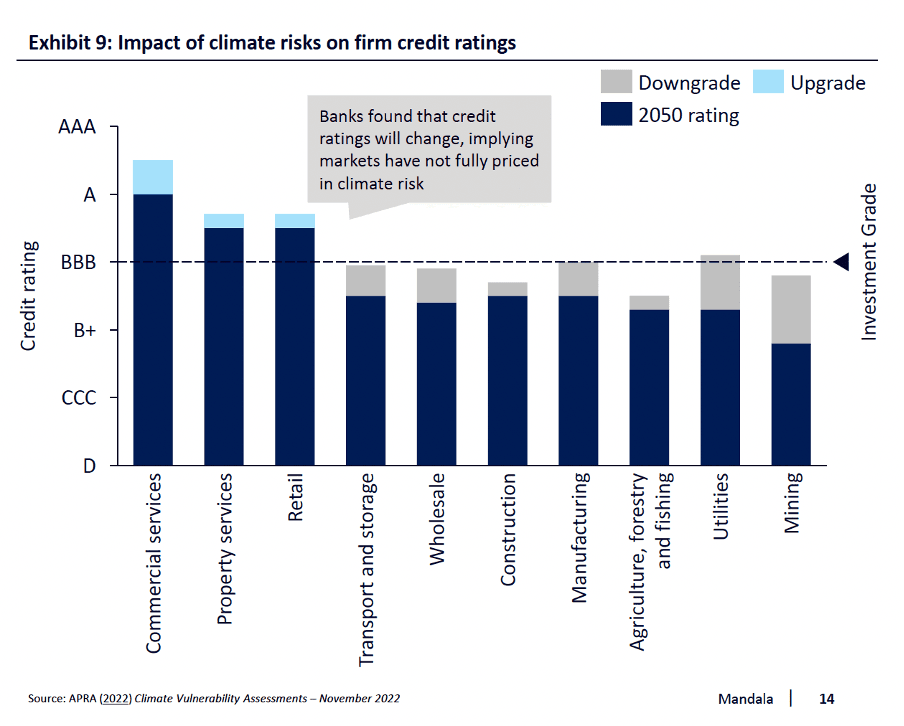

APRA modelled scenarios for Australia based on the work of the Network for Greening the Financial System

The Network for Greening the Financial System is a group of central banks contributing to the development of climate related risk management. In this capacity they developed hypothetical scenarios for how climate change will evolve transition risks and physical risks. APRA then identified two scenarios that Australia was most likely to face.

‘Minimal transition’ scenario: Under this scenario, the world does not adjust sufficiently to avoid a 2 degree increase in temperatures. The future has higher physical risks such as extreme weather events and changing climate conditions which impact businesses and the financial system.

‘Delayed transition’ scenario: Under this scenario, Australia delays the majority of its economic transition until 2030 when it undertakes a rapid reduction in emissions. This has high transition risks as the adjustment of the economy is more disorderly. This scenario includes superannuation regulations preventing capital reallocation.

Recent changes in climate policy will mean Australia avoids high physical risks, but experts believe Australia will still have high transition risks

APRA’s climate vulnerability assessment finds that some sectors benefit under these scenarios while others suffer

In November 2022, APRA coordinated Australia’s five largest banks to conduct a climate vulnerability assessment using the delayed transition scenario to determine the impact of climate risks on credit ratings. The assessment revealed that physical and transition risks can result in negative credit rating impacts and that current credit markets were not fully pricing in these risks.

The impact of the Delayed Transition scenario was prominent, where counterparties from emissions intensive sectors (e.g. fossil fuel extraction and related businesses, mining and certain utilities) were assessed to experience the greatest impact to their credit quality.

Industries that were assessed by the banks as better positioned to transition towards a lower emissions economy, and as a result potentially minimise the impact from external emissions prices, saw more moderate or even positive credit rating impacts.

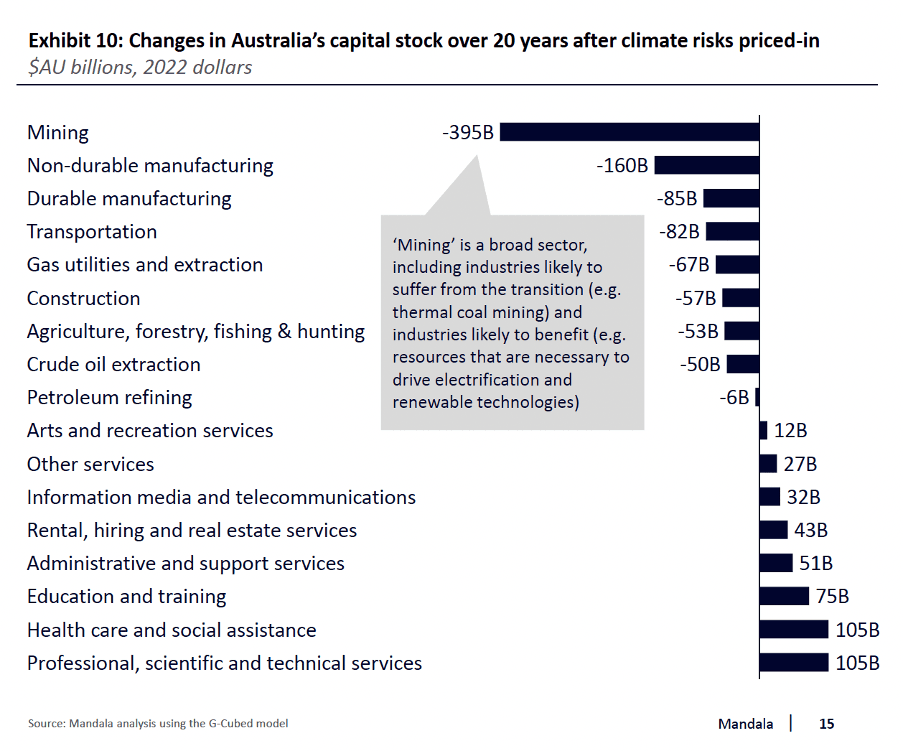

Climate risks result in a significant reallocation of capital across the Australian economy

Mandala modelled the implications of APRA’s credit rating assessments for the Australian economy using the G-Cubed CGE model (Appendix A).

The model found a significant reallocation of capital within the Australian economy under this scenario. The investment reductions were highest in mining and manufacturing between $395B to $245B respectively, reflecting the carbon and capital intensity of the sectors. Crude oil extraction and petroleum found lower reductions despite their carbon intensity. This reflects the relative size of these industries in Australia. The least carbon intensive sector, the services sector, saw a cumulative increase in investment of $450B over 20 years.

This modelling also highlights the harms from delaying Australia’s climate transition. If the rate of change was to increase, capital and businesses would be able to adjust to the clean economy in a more orderly way.

Super funds that seize transition opportunities are likely to get better returns for their members.

If funds aren’t prevented from investing in green assets, the economy will gain $170 billion and 620,000 jobs will be supported

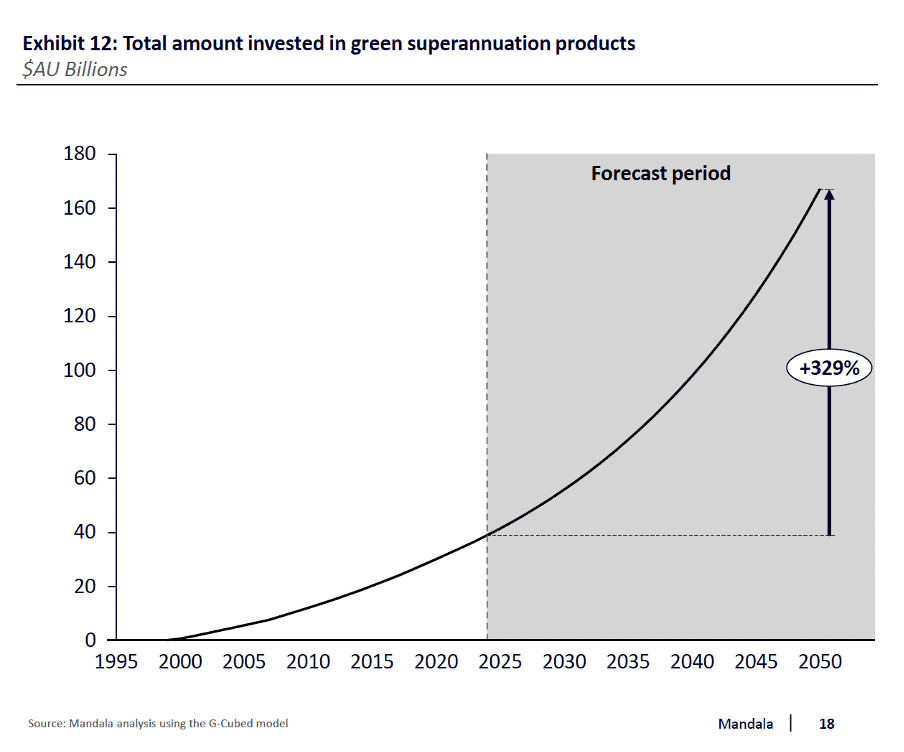

On the current trajectory, an additional $167 billion in super could be invested in green assets by 2050.

The demand for green superannuation products with exclusions in the Choice market has grown exponentially since the 1990s1. In 2022, the total funds under management in these products reached $35 billion. Green products are overwhelmingly Choice funds, these are products that are not the default accounts for members and face fewer regulations. They allow members greater control and flexibility. They currently do not face performance tests; however, they will face them as early as August this year.

If the value of green products grows at the rate of the superannuation industry, more than $167 billion will be invested in green products by 2050. This represents a 329% increase from 2022 to 2050.

However, this $167 billion is at risk. As outlined in the previous section, regulatory pressures are preventing funds from offering these products if YSYF results in the merging of green funds into non-green funds.

Allowing super funds to support the transition produces a more orderly and cheaper climate transition

Regulations that slow the capital reallocation necessary for Australia’s green transition will make that inevitable transition more costly.

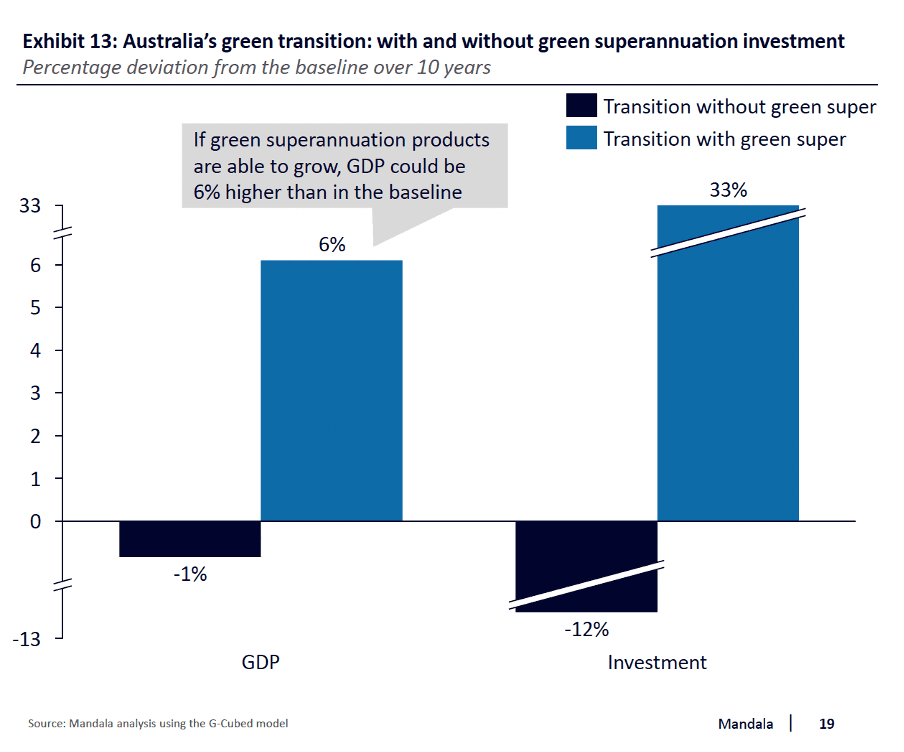

The pricing-in of climate risks results in a significant reallocation of capital in the economy. Capital leaves ‘brown’ sectors and moves towards ‘green’ sectors. This is a costly transition. However, if regulations prevent superannuation funds entirely divesting in brown sectors, the transition will become more costly. The capital reallocation implied by APRA’s forecasts could see GDP contract by 1 per cent and investment contract by 12 per cent over 10 years.

If green superannuation funds are able to grow and support the capital reallocation through exclusions, this will offset this cost. GDP could grow by up to 6 per cent and investment could grow by up to 33 per cent over the same 10-year period. This is compared to a scenario where green superannuation funds are forced to close and their capital is invested in the same way as other superannuation capital currently.

The additional investment spurs GDP growth, wages, investment, and job creation while easing cost of living

The additional investment will help achieve net zero targets by reducing emissions by up to 36 million tonnes

The reallocation of capital in the Australian economy, supported by exclusions and green investment from green superannuation funds, significantly reduces Australia’s carbon emissions.

As Australia’s growth industries shift from polluting industries to green industries, carbon emissions fall by 6 million tonnes in the first 10 years. By way of comparison, Australia’s carbon price introduced under the Gillard government saw emissions fall by 15 million tonnes over a 10-year period.

After 30 years, the cumulative reduction in Australia’s carbon emissions exceeds 30 million tonnes. While the Safeguard Mechanism will do the heavy lifting in reducing Australia’s carbon emissions, green investment by superannuation funds will play an important role in reducing the cost of Australia’s transition while reducing emissions.

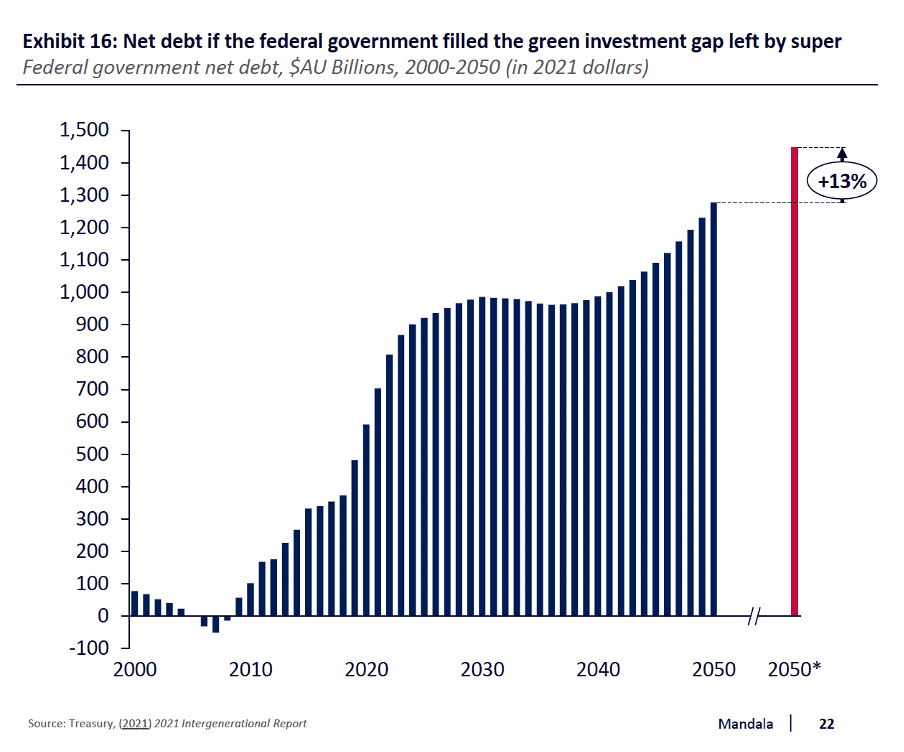

The Commonwealth cannot fund the transition alone; filling the gap left by super would increase net debt 13%.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the decade of budget deficits that preceded it have reduced Australia’s fiscal space.

If the Federal government was to fund the green investment shortfall left by superannuation, federal government net debt would increase by 13 per cent. It would take decades to grow out of this debt, meaning that future generations would likely pay the bill.

If the Federal government didn’t fund the gap, the investment shortfall would be funded by drawing savings from elsewhere in the economy, brought about by higher interest rates. This would add further pressure to the cost of living and would result in the higher-cost transition outlined earlier.

Conclusion

The Your Future, Your Super reforms were well-intentioned. Their goal was to increase member engagement, reduce fees, increase performance, and hold trustees to account for the decisions they make. But the reforms have had unintended consequences and implementation issues.

The current rules make it more difficult for superannuation funds to participate in the green transition and have detrimental impacts on:

- People saving for their retirement: it reduces their retirement incomes by around 1.5 per cent each year

- The national economy: barriers to green investment make Australia’s climate transition more costly

- Our environment: lifting private sector investment will play a critical role in reducing carbon emissions

- Government Budgets: less investment from the private sector means more of the heavy lifting needs to be done by government budgets

Principles for reform

The government is reviewing the Your Future, Your Super reforms to ensure they are fit for purpose. The government should be guided by four key principles in considering these reforms:

1. Benchmarks need to be appropriate for the fund: Benchmarks help savers identify whether their fund is performing well, but these benchmarks need to be appropriate for the fund. The government should assemble a taskforce –including super funds, external fund managements and relevant representatives from the green sector –to identify the appropriate benchmarks in time for the implementation for the 2024 performance test.

2. Benchmarks need to be assessed over an appropriate time period: Assessing fund performance over 10 years can be misleading if the benchmark is a poor fit for the fund especially ones that relate to retirement incomes. More than 20 per cent of the impact of shocks on equity prices occur after 10 years.

3. People should be allowed to invest in line with their values and preferences: Those saving for their retirement should be able to invest in-line with their values and preferences and funds should be allowed to deliver on these choices without being penalized for doing so.

4. Sustainability should not be allowed to be an excuse for poor performance: With the right benchmarks and effective enforcement agencies, we can ensure sustainability is not an excuse for poor performance.

Download the full report here.

Read our latest posts

Restoring affordable access to specialist care in Australia

In this report, Mandala and Private Healthcare Australia (PHA) studied the affordability of specialist care in Australia. We find that specialist fees are rising, exacerbating cost-of-living pressures on consumers and worsening the affordability of healthcare. We propose a targeted package of measures to improve consumers' ability to access high-quality care, of their choosing, at fair and transparent costs.

3 Feb, 2026

Critical Minerals Strategic Reserve Design

Mandala's latest report for the Association of Mining and Exploration Companies (AMEC) sets out an industry-informed approach to implementing Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategic Reserve, with a focus on rare earths critical to national security and the energy transition. Bringing together 10 Australian rare earth developers, and drawing on international precedents and economic analysis, the report recommends a commercially viable and fiscally sustainable model to support new investment in Australia’s rare earths sector while managing risk to taxpayers.

12 Jan, 2026

The Value of Online Payments to New Zealand Businesses

Mandala partnered with Stripe on a research report based on the findings of a survey of 200 New Zealand businesses around the value of online payments and opportunities for future innovation.

18 Dec, 2025

Optimising Australia’s Specialist Investment Vehicles for the Net Zero Journey

Mandala, in partnership with IGCC, explores how Australia’s Specialist Investment Vehicles (SIVs) are deploying public capital to accelerate the net zero transition. The report examines the current funding landscape, identifies structural challenges that limit the effectiveness of public investment, and sets out a pathway to evolve the SIV system into a more coordinated, capital-led model aligned with national priorities.

10 Dec, 2025